De Haas–van Alphen effect

The de Haas–van Alphen effect, often abbreviated to dHvA, is a quantum mechanical effect in which the magnetic moment of a pure metal crystal oscillates as the intensity of an applied magnetic field B is increased. Other quantities also oscillate, such as the resistivity (Shubnikov–de Haas effect), specific heat, and sound attenuation.[1][2] It was discovered in 1930 by Wander Johannes de Haas and his student P. M. van Alphen.

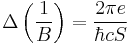

The period, when plotted against  , is inversely proportional to the area

, is inversely proportional to the area  of the extremal orbit of the Fermi surface, in the direction of the applied field.[3]

of the extremal orbit of the Fermi surface, in the direction of the applied field.[3]

where S is the area of the Fermi surface normal to the direction of B.

This effect is due to Landau quantization of electron energy in an applied magnetic field. A strong magnetic field — typically several teslas — and a low temperature are required to cause a material to exhibit the dHvA effect.[4]

In 1952, Lars Onsager explained the physics behind the effect, and, due to his interpretation, this effect can be used to image the Fermi surface of a metal, to measure the carrier density and more , which makes this a very powerful probing technique in condensed-matter physics.

References

- ^ Zhang Mingzhe. "Measuring FS using the de Haas-van Alphen effect". Introduction to Solid State Physics. National Taiwan Normal University. http://phy.ntnu.edu.tw/~changmc/Teach/SS/SSG_note/grad_chap14.pdf. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- ^ T. Holstein (1973). "de Haas-van Alphen Effect and the Specific Heat of an Electron Gas". Physical Review B 8: 2649. Bibcode 1973PhRvB...8.2649H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.8.2649.

- ^ C. Kittel (2005). Introduction to Solid-State Physics (8th ed.). Wiley.

- ^ N. Harrison. "de Haas-van Alphen Effect". National High Magnetic Field Laboratory at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. http://www.lanl.gov/orgs/mpa/nhmfl/users/pages/deHaas.htm. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

External links

- M. Suzuki, I.S. Suzuki (26 April 2006). "Lecture note on Solid State Physics: de Haas-van Alphen effect". State University of New York at Binghamton. http://www2.binghamton.edu/physics/docs/note-dhva.pdf. Retrieved 2010-02-11.